In 2024, I organized a philosophy retreat in Salamanca, Spain. It was a trial run to explore the feasibility of the idea, and how well it would pan out for the participants. The retreat went better than I would have expected, thanks in large part to the enthusiasm and great engagement of the participants.

Encouraged by the initial outcome, the second trip took place over the weekend of November 6–9, 2025. We gathered again, this time in Madrid, to disconnect and explore the city’s cultural heritage, focusing on the philosophy of José Ortega y Gasset.

These gatherings are kept small, capped at no more than five or six people, to ensure an intimate setting, allowing everyone to enjoy the various activities together and participate in the ongoing dialogue that lasts throughout the trip.

Perhaps “cultural tour” is a better description than “retreat.” In reality, it’s somewhere in between.

Program Highlights: Cultural Immersion in Madrid

This year’s event kicked off with a philosophy walk to explore the parts of Madrid most relevant to Ortega and his philosophy, including the Ateneo, the Círculo de Bellas Artes, the Casa del Libro building (which hosted Ortega’s magazine Revista Occidente), and the Museum of Romanticism, among others.

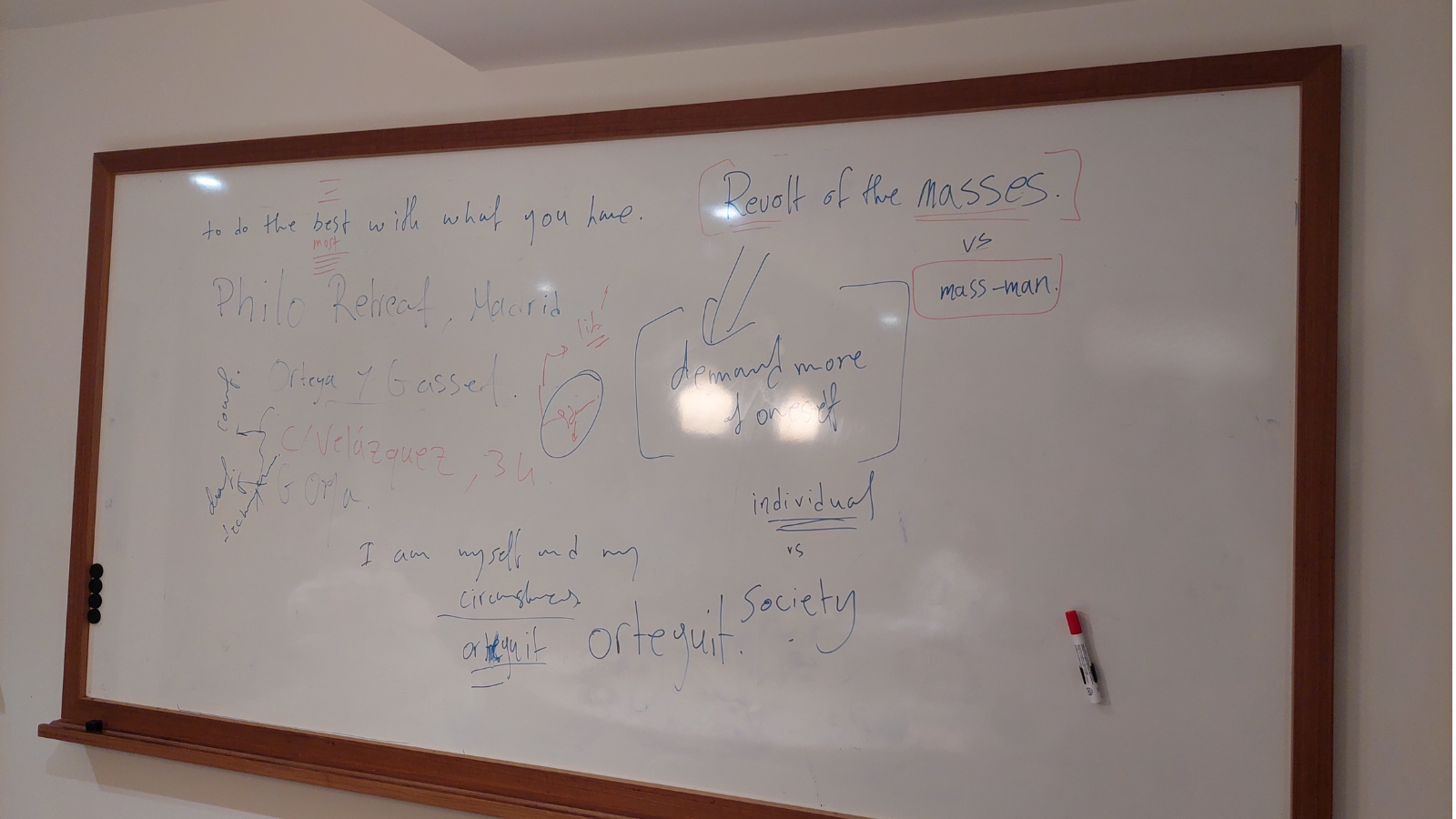

We also held a workshop where we discussed Ortega’s philosophy, focusing mainly on two of his books: The Revolt of the Masses and What is Philosophy?

On the second day, we visited the Lázaro Galdiano Museum, which displays the amazing and exquisite collection of Spanish financier and art collector José Lázaro Galdiano. Galdiano’s extensive collection, which included 12,000 items when he died in 1949, was donated to the Spanish government. It includes a variety of works from different periods, including paintings by Goya, Velázquez, and Bosch, among others.

We also had a fantastic cheese tasting activity at Formaje, a small, charming shop with cozy aesthetics and great vibes. They curate cheeses from Spain and around the world, sharing their enthusiasm for artisanal cheese and supporting small-scale traditional cheesemakers.

Following these cultural and culinary explorations, the trip culminated in an evening dedicated to focused philosophical exchange. Over drinks, the participants shared a brief discourse on a topic they had agreed upon, in the spirit of Plato’s Symposium.

The main question was, “What Is Art, and Why?” a question Ortega addresses in his seminal essay The Dehumanization of Art. The speeches of the three participants were followed by an extensive exchange that examined and synthesized ideas from the previous conversations.

Thematic Approach: Concentric Inquiry

This year, the initiative focused on three main aspects present in Ortega’s thought and writings: philosophy and the cultural scene (What is Philosophy?, The Dehumanization of Art); education (The Mission of the University); and political analysis and political life (The Revolt of the Masses).

To immerse ourselves in Ortega’s philosophy and grasp what he meant by “I am myself and my circumstance” (the main theme of the retreat), the approach involved moving in literal and metaphorical concentric circles to zoom in on his ideas. This exercise is inspired by the very same approach Ortega explained in his What is Philosophy?

During these philosophical and cultural walks, the workshop, and the meals and symposium, we had the chance to reflect on Ortega’s main ideas in today’s context. Each participant reflected on their “myself and my circumstances” from a personal, professional, and philosophical perspective.

The method of concentric inquiry helped us zoom in on the fundamental tensions addressed by philosophers from Plato until today (with nuances conditioned by the respective context of each).

The Societal Balance

This inquiry centers on finding a good balance between the smallest unit and the largest unit within a society — be that the individual, family, community, or society. At the core is also the tension between beliefs, opinions, and knowledge.

What seems to work anecdotally at an individual level doesn’t necessarily transfer to a more complex environment. As a result, while it might be easier for a person to cruise through life holding false beliefs (avoiding extreme violent cases, of course), when others are involved, all the way to governing a group of people, things become more difficult. Here, the question of knowledge becomes more pressing. Ortega spends some time fleshing this out in his book, What is Philosophy?

The Individual’s Life Project

At an individual level, the tension lies in how to live a good life while simultaneously being a good citizen (whatever this means). One’s life project, individual liberty, taste, opinions, beliefs, knowledge, the unconscious, consciousness, and interaction with others are in constant movement, and the ultimate direction, if there is one, is not always clear.

We find ourselves born into life (“radical life,” as Ortega calls it), and we are almost forced to make sense of it. That’s what distinguishes humans. Somehow, as a species, we managed to settle into communities and learned how to utilize nature to create civilizations.

This is not something to be taken for granted, according to Ortega, because it requires a great deal of discipline, learning, and knowledge of history, science, technology, art, and philosophy. To avoid stagnation, as individuals, we need to demand more of ourselves.

Underlying all these processes is a creative force, which is channeled through art, science, literature, and philosophy. We strive to express ourselves, make sense of the world, build things to understand ourselves and reality, and put what we build into good use, making our lives slightly easier.

Art as the Organ of Philosophy: Schelling’s Perspective

This is where art comes in. And I’ll use Schelling instead of Ortega here. For Schelling, art is a creative process through which we express ourselves and simultaneously learn a great deal about ourselves. According to him, it is the organ of philosophy because art provides a playful space where we can speculate, combine ideas, and explore concepts for which we don’t yet have clear language.

As such, art and the imagination are the driving force behind creativity and cultural evolution. Art, for Schelling, takes many different forms. From the ancient epics to the modern novel of his time (the 1800s), encompassing music, sculpture, and more, and in our time, cinema, and so on.

We push the boundaries with art in all its forms, and it allows us to, as mentioned, express ourselves, while also giving free rein to the imagination to do its magic. Every now and then we create something radically new. As such, science fiction often becomes a reality after a few decades.

These discussions will be continued in next year’s trip, which will most likely be held in Vienna, the home of Hayek, Freud, Adler, Frankl, Feyerabend, and the Vienna Circle.